During my childhood, I spent every summer in Brittany, on a small island without running water or electricity. I learnt to economise on resources. So I don’t feel out of place when I find myself at the end of the world, on a fairly isolated farm with no mod cons. I feel good. I don’t miss anything, other than what is superfluous.

A time to talk with bloggers

I love spending time with tea producers, but I also really enjoy talking to our customers or, as I did this week at our Rue Vieille-du-Temple store, with bloggers who had come to discover and taste our latest creations: Les Jardins. I spoke about how gardens were a source of inspiration; the joy of walking through a favourite garden in different seasons; how these new infusions can be enjoyed hot, at room temperature, or iced. Of course, we also talked about “grand cru” teas, and food too.

Manual skills are still essential in tea production

In most tea-producing countries, the best teas are plucked by hand. This means that growing high quality tea often requires the participation of many men and women. Not only is harvesting the leaves a meticulous task, but sorting them just before they are packed and dispatched is also done by hand. The work demands incredible patience.

After rice, tea is the agricultural resource that employs the greatest number of people around the world.

Pairing tea and cheese: the example of goat’s cheese

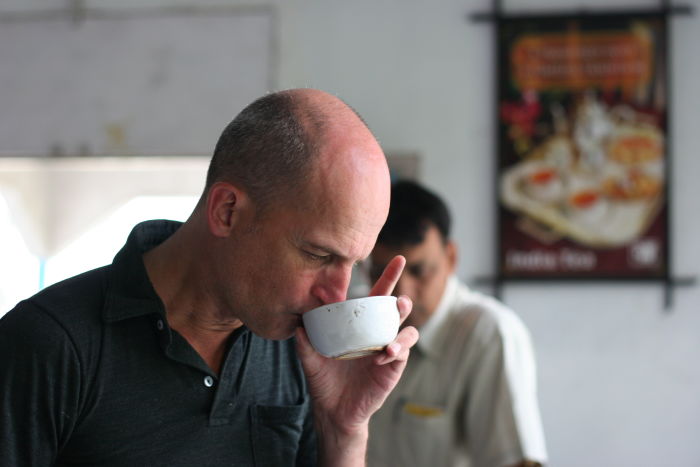

Pairing tea and cheese: the example of goat’s cheese Fresh goat’s cheese is one of my favourite cheeses, and I like going to the farm to choose mine. I prefer to accompany it with tea rather than wine. More precisely, a Premium Bao Zhong served at room temperature. To prepare it, first steep the tea for six minutes, then remove the leaves from the pot and leave it to cool for 30 minutes. Serve in small clear liqueur glasses. It will make an interesting change for your guests, and you will love the pairing: the tea does not overwhelm the subtle flavour of the cheese; on the contrary, it accompanies it, as the tea’s vegetal and floral notes make way for the milky, delicate animal qualities of the cheese. They make a fine match.

It also rains elsewhere in summer

If you are finding the temperatures a bit cool this month, take note that that Western Europe is not the only place where it’s raining. In Northern India and Nepal, July and August are rainy months. It can rain for days on end, but people carry on working unperturbed. Or they take a break for a natter with friends.

Knowing how to appreciate bitterness

Bitterness is the only intelligent flavour, Olivier Roellinger told me as we tasted a selection of teas together, when I warned him that some darjeelings have a touch of bitterness.

It is a flavour that, unlike sweetness, needs winning over, taming. It can be off-putting, but when we know how to appreciate bitterness, it offers such richness, such delight!

And Olivier Roellinger talked to me about the famous Italian gastronomy, a fine example of a bitter cuisine.

Nepal is leading the way in new teas

Among the “Grands Crus” I’ve tasted in recent months, among the many teas from every part of Asia, I have to say that the ones that have impressed me most are the teas from Nepal. Of course, I have been sent wonderful Ichibanchas, unique first-flush Darjeelings, exceptional Oolongs from Taiwan, and richly aromatic Long Jings. Nonetheless, what is happening in Nepal is unique. In the past decade, this country has been working hard to produce teas of a very high quality. And unlike what I see in other countries, where there is a tendency to perpetuate a highly respectable tradition, here people are trying to develop new teas, work with different cultivars, experiment with wilting and rolling methods, and so on. And often, with success.

Loving tea means loving the world

When I visit a plantation, when I go to see a producer, I naturally spend time tasting the tea. But I also look at the growing conditions. I want to find out if the tea is produced cleanly, if nature is respected. For me, loving tea also means loving the ground in which it grows. The tea I drink, the tea that does me good – I don’t want it to harm the earth, or those who grow it. That’s why I also visit the clinics, nurseries and, of course, schools.

L’appel du Grand Bleu

Vous êtes nombreux en cette période estivale à vous mettre au vert pour quelques semaines. Au vert, je vous y invite tout au long de l’année à travers mes billets, à travers mes photos, à travers ces champs de thé qui ondulent à perte de vue. En cette saison de transhumance, je vous invite cette fois-ci au bleu plutôt qu’au vert, je vous emmène sur les rives de mon lac préféré, le lac Inlé (Myanmar), pour vous souhaiter de belles semaines de vacances !

The tea plant that didn’t stop growing

Due to the harvesting of its leaves, a tea plant does not get bigger; instead its trunk thickens. So a tea field looks more like a bonsai forest. But left unchecked, Camellia Sinensis and Camellia Assamica can grow to a height of several metres. Here is Rudra Sharma, the planter at Poobong in India, in front of one of his wild tea plants.