I came to photography late in life, and the first piece of advice I got was to make sure the sun was always behind me to illuminate people’s faces. Twenty years later, I still can’t bring myself to follow that advice. When the sun is out, I naturally turn toward it and often end up with backlit photos, which I like. And when it’s overcast, I still manage to face toward the light source—in this case, the sky—so that my figures always appear slightly mysterious.

Contemplating and Photographing

I came to photography through necessity, and 20 years later I find myself enjoying it a great deal. When Palais des Thés was new, I would travel through Asia without a camera. I came back from my trips with an eyeful of gorgeous landscapes, but not a single image to share with my employees or my customers. Back then, I believed you had to choose between contemplating a scene and photographing it. Now I realise that’s not the case at all. Today, I take the time to contemplate a scene and choose the best angle, and then I linger, motionless, while waiting for just the right light.

About the selection of Chinese new-season green teas

This year, I have chosen ten Chinese new-season green teas. They include well-known names such as Bi Luo Chun, Long Jing, Huang Shan Mao Feng, Ding Gu Da Fang and Yong Xi Huo Qing, as well as some rare pluckings. There are three aims with a selection like this: the teas must be exceptional, clean, and offer value for money.

I’ve travelled enough in China over 30 years to know where to find the best teas. However, every year, more and more Chinese people are buying these rare teas, and domestic demand has gone from non-existent to high, which has, of course, pushed prices up. Also, although European standards on pesticide residues are the strictest in the world, which is a good thing, they put off a number of farmers due to the long, costly analysis process involved, first in China, then in France.

So the 2019 Chinese new-season selection features teas that are rare, clean and the best possible value for money. Happy tasting!

A bit of shade

When it gets really hot, tea plants benefit from a few hours of shade every day. So in regions where temperature can soar, trees are planted above them.

We are like the tea plants – dreaming, as we walk around town, of leafy trees that would shade us from the sun and excessive heat.

A wet shirt

Lotus tea is a Vietnamese tradition. To grow the flowers, you have to get wet. You get wet when it’s time to harvest the flowers. You get wet in the pond, either wading through the chest-height water or in the little leaky boats. And you get wet when it’s time to divide up Nelumbo nucifera by plunging your hand down towards the bottom and grabbing a few rhizomes, which will be planted out in another pond.

Lotus tea: a Vietnamese tradition

The lotus flower plays a very important role in Vietnamese culture. So it’s not surprising that the country has a tradition of flavouring tea with the flower, resulting in a particularly sought-after beverage. Production takes place in June and July and requires patience, as the tea leaves are left in contact with the flower pollen for five days in a row.

A Hmong woman

The Golden Triangle is a fascinating region thanks to its varied geography, mountains covered in jungle, hidden valleys and, most of all, the many and varied ethnic groups who have made it their home. Each ethnic group has its own culture, language and customs. From one to another, the styles of houses change, their relationship with the land changes, the food changes. Here in Sung Do, in northern Vietnam, a woman sets out to pick tea leaves from hundred-year-old trees.

Harvesting in the treetops in the Golden Triangle!

In the region known as the Golden Triangle, you can find tea plants that are not quite like the others. Instead of being pruned at a low level to make it easier to pick the leaves, they are left to grow like trees. When harvest time comes, the pickers must climb up into the camellias, some of which are several hundred years old. The leaves from these trees are particularly sought-after to make Pu Erhs and dark teas.

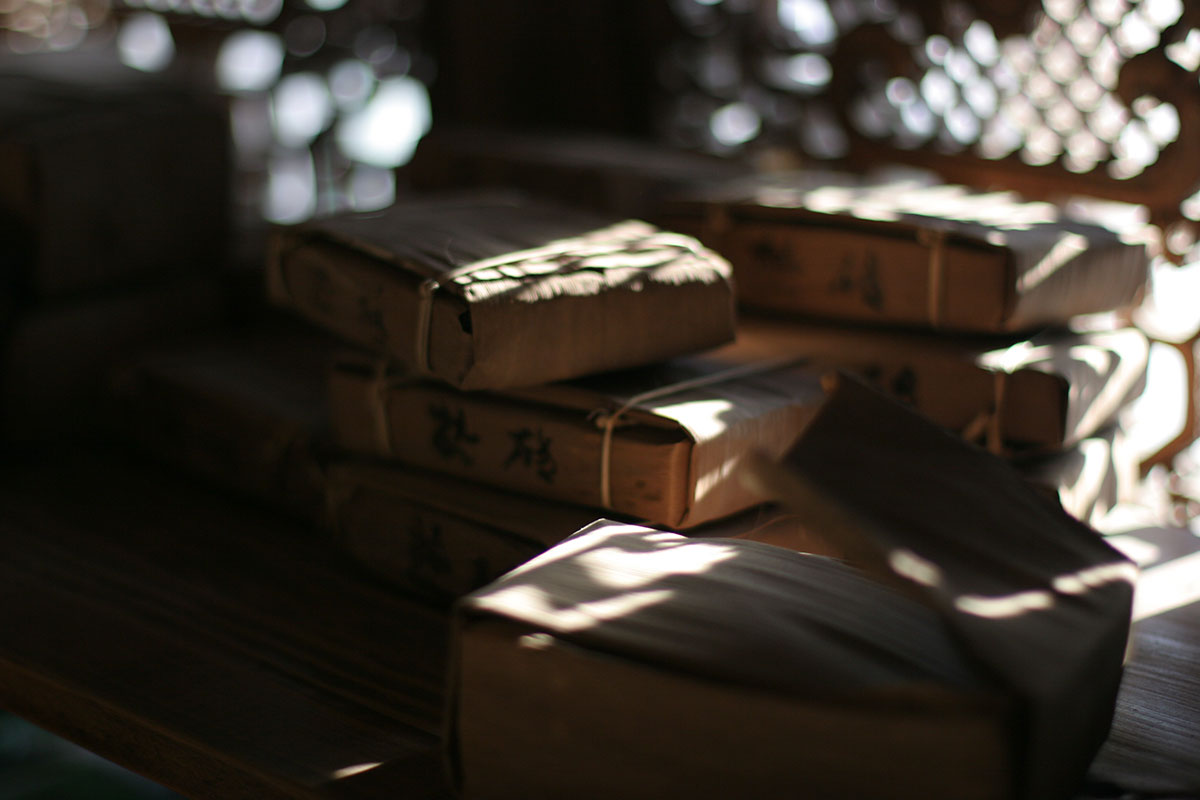

Chinese machines launched the Nepalese revival

Nepal has been producing tea for nearly two centuries. Originally, the culture and organisation of its plantations were based on the model that existed in Darjeeling. But since then, things have evolved considerably. Just over 10 years ago, a number of enthusiastic tea producers wanted to see how things were being done elsewhere, and brought back from Taiwan and China various small-capacity machines that offer a different and much more artisanal solution for processing tea. Today, these machines are widely used in most of the country’s tea co-operatives. Thanks to their introduction and the dedication of the people who use them, we can now enjoy all sorts of teas from Nepal: white, semi-oxidised, shaped into balls… And from a tasting perspective, they are of a remarkable quality.

This revival of Nepalese tea that we’ve seen in the last decade stems from a break with the old British system.

Sharing

Sharing. What is better in life than to share? My job as a tea researcher is all about sharing, creating a link between the farmer who makes the tea and the enthusiasts who drink it. Passing on knowledge as it’s acquired. Sharing with one’s team, inviting them to visit the tea fields and farms, involving them in unique occasions, memorable time spent with villagers who are so kind and hospitable, so immensely generous.

Here, in Ilam valley in Nepal, I’m visiting the plantations of La Mandala, Pathivara, Tinjure, Shangri-la, Arya Tara and Panitar in the company of Carole, Fabienne, Oxana, Sofia, David, Léo and Mathias.