When you taste a large number of teas that are particularly tannic and astringent, you have to decide whether to swallow or not. In order to protect their palate, a taster will swill the liquor around in their mouth to analyse it, then spit it out. This allows them to remain neutral when assessing the next sample.

Tea Tasting

Choose loose-leaf!

If you’re someone who thinks about the health of our planet and you want to reduce your use of packaging, you might consider what benefit there is in using a tea bag instead of loose-leaf tea next time you’re brewing a cuppa. It’s true that when we’re on a flight or staying in a hotel it’s nice to have our favourite tea to hand, and it wouldn’t be convenient to carry around a canister.

But at home or at work, it’s so easy to use a teapot or a mug with an infuser. Tea bags are practical, of course. But it’s not difficult to measure out tea leaves: a pinch between three fingers is about right for a 10cl cup. Then pour over the hot water. So simple. And it does away with one, two or even three layers of packaging.

Teas to sip by the fire

Now the temperatures have dropped, we want to drink different types of teas from those we enjoyed in warmer weather. This season calls for rounder, fuller liquors; warm, woody notes; spicy and stewed fruit flavours. Here are some suggestions for teas to sip by the fire. Try a Jukro from South Korea for its cocoa notes, a Chinese Qimen Hong Cha Mao Feng for its leather notes, a Dianhong Jin Ya for its honey notes, a Dongyan Shan Tie Guan Yin from Taiwan for its stewed fruit notes, a Japanese Shiraore Kuki Hojicha for its toasted notes, and a Spirit of Smoke from Malawi for its smoky notes.

The right infusion temperature

When you’re travelling, you sometimes have to boil water to purify it. For tea, that’s obviously not ideal, especially as some teas need to be infused at 50°, 70° or 80°C. Here is a simple method to reach the correct water temperature for your tea (this will be marked on the packaging of any decent tea merchant). When your water has boiled, pour it into a recipient. The water temperature will drop by 9°C. Then pour it into another; it will drop by 9°C again. And so on.

Frédéric Bau, pastry chef and chocolatier, founder of the Valrhona School

Drinking and tasting tea with people who specialise in a different product is fascinating. Whether your work revolves around tea, chocolate, olive oil, wine or any other fine ingredient, the tasting techniques are the same. But the experience differs in that each substance has its own range of aromas, textures and flavours. We’re like musicians who play different parts but all share a love of music.

I was lucky enough to receive a visit from Frédéric Bau. Frédéric is one of the great pastry chefs, as well as the founder of the Valrhona School and the Creative Director of Valrhona. Together, we tasted eight premium teas, infused at room temperature.

It was a wonderful opportunity to share our impressions and talk about our passions.

All my favourite teas

I’m often asked what my favourite tea is, and the question always makes me nervous. Each time I have to think about what to say. Someone who doesn’t know much about tea might say they like a certain type of tea, and someone else might name a different type. But when you have the incredible and very special opportunity to taste the best teas in the world throughout the year, like a top sommelier drinking wine, how is it possible to name just one?

When you’ve tasted so many teas of each type, they become part of you. You get to know them from every angle, you discover their unique characteristics, their point of equilibrium, their harmony. You’re the best placed to appreciate them. This applies whether it’s a lightly oxidised Taiwanese Oolong, a First-Flush Darjeeling, an Oriental Beauty, a Japanese Ichibancha, a new-season Chinese green tea, a hand-rolled Nepalese tea, a black Chinese tea such as a Qimen or a Yunnan, a Rock tea or a Phoenix tea, a dark tea from China, Africa or elsewhere, a Mao Cha plucked from hundred-year-old trees or a Gao Shan Cha, to name just a few. You’re the best placed to appreciate them and the worst placed to pick just one.

So if you meet me, please be kind and don’t ask me to name my favourite tea. Instead, ask me what I love about this tea, or that tea, ask me about the feelings they evoke. Talk to me about the great variety of sensory and emotional responses instead of restricting me to a few.

The aromas of tea

Smell is probably the richest sense in terms of tasting. Food and drink have a smell, or rather a number of smells, which we perceive while tasting, especially if we practise retronasal olfaction by breathing air out through the nose while the substance is in the mouth. In the case of tea, there are many aromas. As we’ve done since childhood with naming colours (red, blue, yellow, etc.), we can categorise aromas too: vegetal, fruity, floral, marine, spicy, woody, undergrowth, buttery/milky, mineral, burnt, animal, and so on.

So the next time you drink tea, ask yourself whether its dominant aromas are floral, fruity, animal or marine, etc. Happy tastings!

The textures of tea

Touch is one of our senses, and it plays a part in tea-drinking. In the mouth, we notice the temperature of the liquid, and also its texture, thanks to our sense of touch. A tea can create the impression of being oily or dry. Some Japanese teas or Taiwanese oolongs, for example, give the impression that the liquid in the mouth is almost creamy in texture. On the other hand, many teas create a sensation of dryness, which we call astringency. Astringency gives a tea its long finish in the mouth. There is no one ideal texture. It’s all about the balance between a tea’s aromas, flavours and texture.

Flavours of tea

When we eat or drink something, we pay attention to its appearance and colour, of course, but once it is in our mouth, we consider the flavour, texture and aroma.

There are five flavours, or taste elements: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and a fifth, lesser known taste, called umami. Tea does not naturally have a salty flavour, but all the other taste elements are present. A tea can have several flavours. Just as an orange is both sweet and sour, a pu erh can be both sweet and umami.

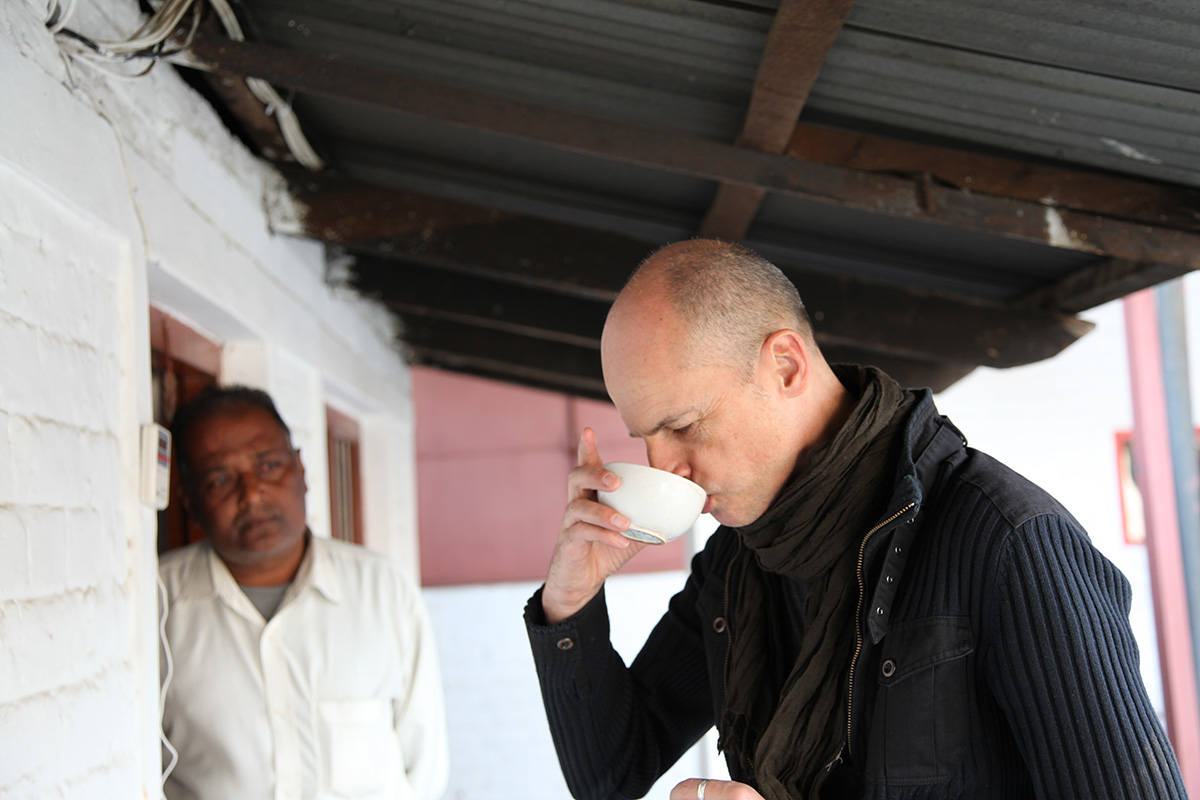

Tasting tea outdoors

A visit to a tea plantation always includes a tasting. This one took place in the dedicated tasting room, with light coming in from outside. Sometimes though, tastings can take place outdoors if the factory is too small, or doesn’t have the right equipment. With a bit of luck you can enjoy magnificent scenery while swirling the liquor around in your mouth. Here, in Pathivara (Nepal), a lovely stone table is used for tastings.