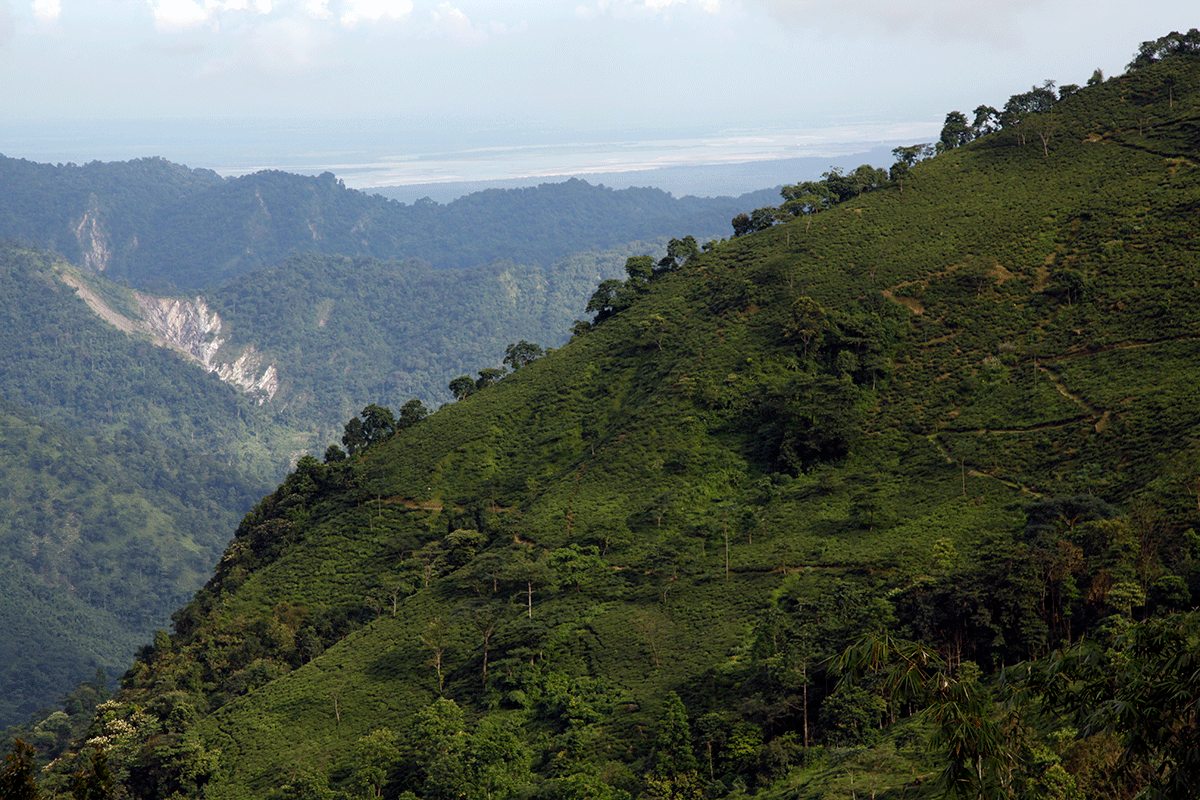

Tea plantations sometimes change hands, and this is important knowledge for tea researchers. The Singbulli garden (photo) in Darjeeling has just been sold. Who will be the next planter? What knowledge of tea will they have, and what production methods will they use? These questions show that you cannot rely on a garden’s name alone. The life of a tea estate evolves, and with it the quality of the teas it produces. Let’s hope that Singbulli continues to make the delicious teas to which we have become accustomed, such as those fine teas produced using cultivar AV2 and on the best plot: Tingling.

From plant to cup

Around the mountainside

It will be another few months before we start returning to normal life, meeting up with friends and family, getting together for a cup of tea, a meal, a glass of wine. Meanwhile, this is the image that comes to mind when I think about the difficult times we’re going

Do the right thing

Our compatriots sometimes use the services of an American company to obtain a book they could easily buy from their local bookshop; they pay someone in San Francisco for goods instead of independent retailers and artisans. The same goes for food: our local shops, cafes and restaurants are so desperate for our support.

When it comes to tea, don’t expect me to bypass the people who count. Palais des Thés sources its teas from producers it knows. It pays them directly, whether the farmer is in a remote Nepalese village, on a high plateau in Malawi, or on a Japanese island. It gives us great pleasure to support the wellbeing of the people involved in producing such delicious treasures. Let’s support good tea and do the right thing.

Beneficial pain

With so much focus on the benefits of the vaccination needle, despite its brief sting, I wanted to look at a comparable phenomenon that affects the tea plant, in which momentary “pain” is beneficial. In some parts of the world, such as Taiwan and Darjeeling, a particular insect – a type of leafhopper called Jacobiasca formosana – likes to munch on the leaves of Camellia sinensis. The plant’s chemical response to this attack results in a rare, highly sought-after aroma in the cup. You will find this bouquet in an Oriental Beauty, for example, or a Darjeeling Muscatel. In these regions, farmers actively protect the insect to make sure they visit the plants and eat their leaves.

Papayas and tea

People are always experimenting, and when you’re lucky enough to be a tea researcher, you’re well placed to see all sorts of things. Here, on a coffee plantation in Tanzania that has branched out into growing tea, there is no lack of innovation. The latest initiative is to remove the flesh of papayas and fill the skins with a semi-oxidised tea that has been withered and rolled. After a short oxidation, the wet leaves are stuffed into the hollowed-out ripe fruit and become impregnated with its delicious scent.

Travels with tea

I met Sidonie when she invited me to be on her RTL radio show. That was a few years ago. We stayed in touch and, after chatting over a cup of tea one day, we thought, why not? Why not combine our passions and take our listeners, tea enthusiasts, on a journey to their favourite tea-producing country? This idea led us to launch a new podcast, or balado, as our Quebecois friends would say.

Join us at https://www.palaisdesthes.com/fr/podcast/ and on your usual podcast platform. These tales of travels and tea are for you. (In French only.)

Around Maskeliya Lake

Would you like to come for a walk with me around Maskeliya Lake in Sri Lanka? Here, we’re halfway between the high-grown and low-grown teas; between those from the mountains of the Nuwara Eliya region and the often-remarkable teas produced in the jungle around Sinharaja forest further south. This is the view from the front of the bungalow on the Moray Tea Estate. The artificial Maskeliya Lake is surrounded by tea plants and the magnificent flora particular to this region, including flamboyant cassia and poinsettia. The yellow and red brighten up the eternal green of our camellias.

A walk in the woods

During lockdown, it can be easy to let ourselves go a bit. We might exercise less and put on weight. Could this be a good time to turn to tea? According to traditional Chinese medicine, one of the many properties attributed to our beloved Camellia sinensis is fat-burning. This remarkable quality is particularly true of dark teas, called Pu Erhs, with their powerful notes of undergrowth and humus. If you can’t take a walk in the woods, you can at least enjoy all the associated aromas in your cup – alongside those other supposed benefits.

Stronger, more robust tea plants

It’s not just us humans that are attacked by viruses; tea plants are too. For them, it is the job of research centres to find remedies for diseases. Of course, this doesn’t involve vaccines, as it does for humans. It’s about identifying the strongest plants and crossbreeding them to create new stronger, more robust plants.

Kangra Valley

Today I’m taking you to Kangra Valley, which lies between the states of Punjab and Kashmir, in India. The British established tea plantations there in the second half of the 19th century.

In 1905, a terrible earthquake devastated the estates, and our British friends abandoned production, fearing that the earth would open up again. More than a century later, the same plantations are thriving. The tea harvested there has improved significantly over the years, and there has been no major earthquake since.