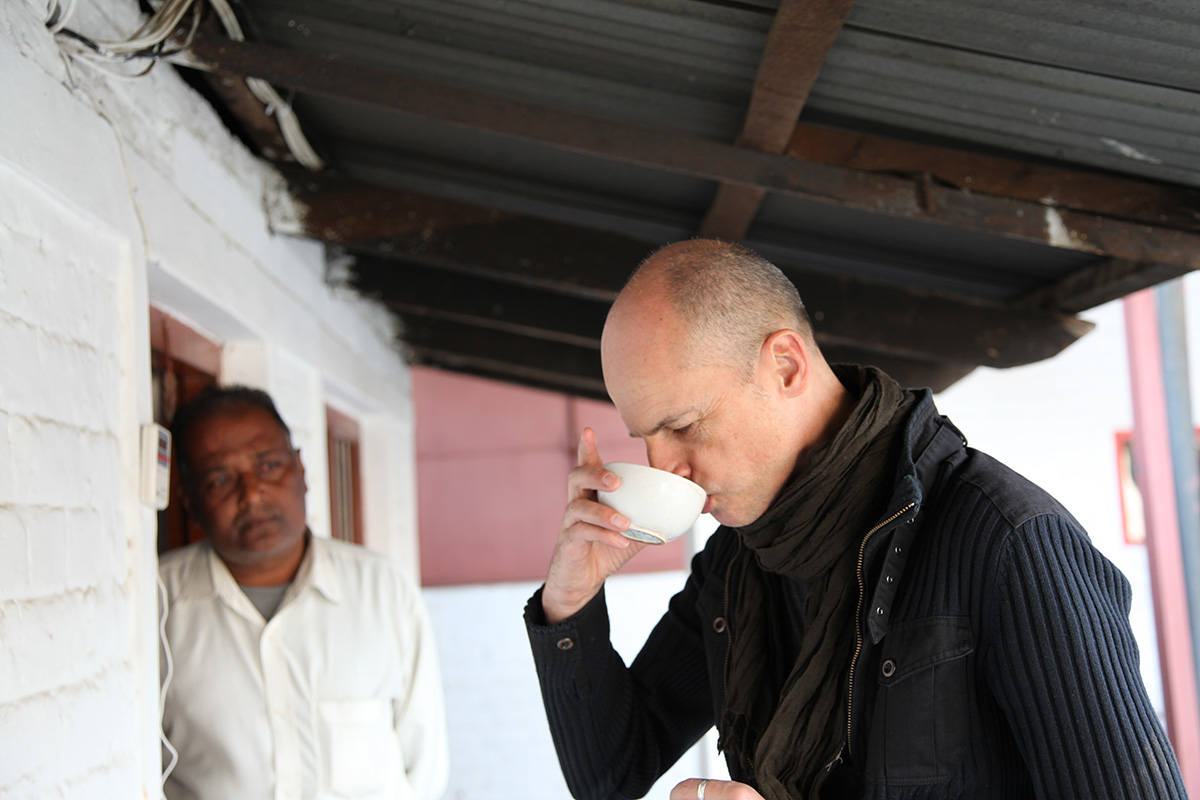

I’m often asked what my favourite tea is, and the question always makes me nervous. Each time I have to think about what to say. Someone who doesn’t know much about tea might say they like a certain type of tea, and someone else might name a different type. But when you have the incredible and very special opportunity to taste the best teas in the world throughout the year, like a top sommelier drinking wine, how is it possible to name just one?

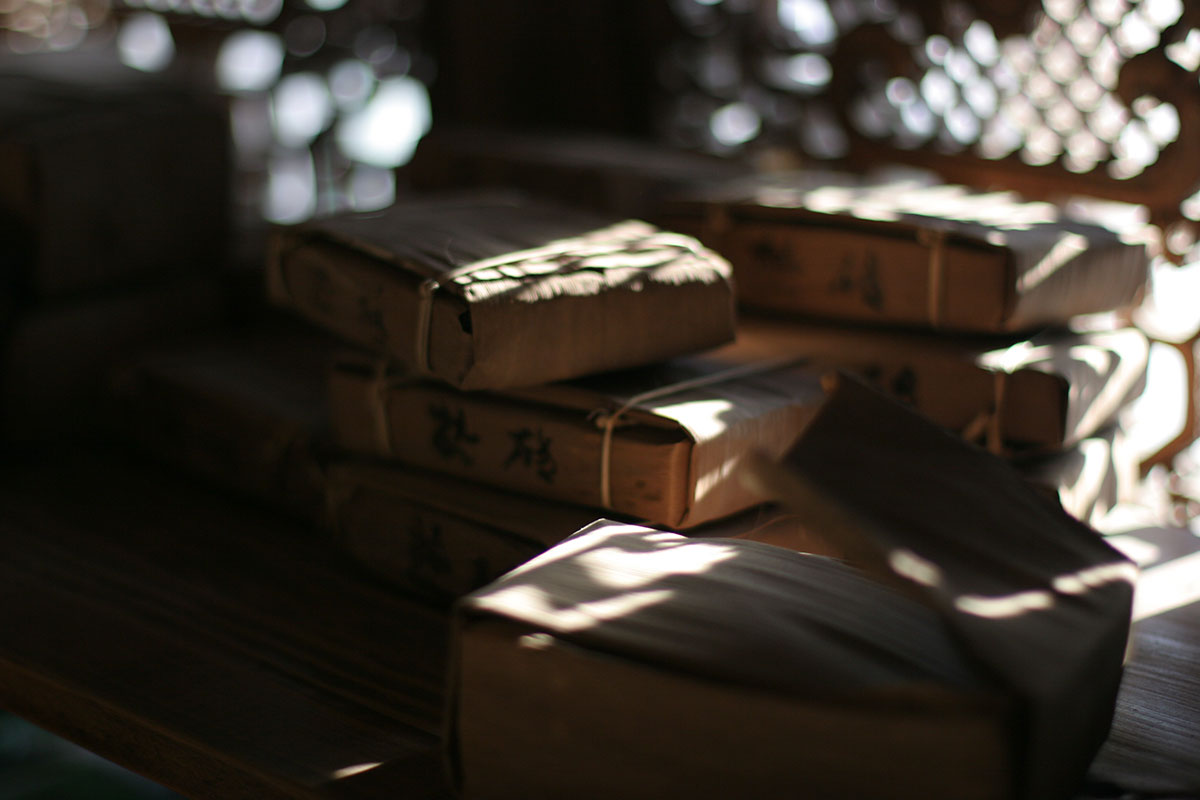

When you’ve tasted so many teas of each type, they become part of you. You get to know them from every angle, you discover their unique characteristics, their point of equilibrium, their harmony. You’re the best placed to appreciate them. This applies whether it’s a lightly oxidised Taiwanese Oolong, a First-Flush Darjeeling, an Oriental Beauty, a Japanese Ichibancha, a new-season Chinese green tea, a hand-rolled Nepalese tea, a black Chinese tea such as a Qimen or a Yunnan, a Rock tea or a Phoenix tea, a dark tea from China, Africa or elsewhere, a Mao Cha plucked from hundred-year-old trees or a Gao Shan Cha, to name just a few. You’re the best placed to appreciate them and the worst placed to pick just one.

So if you meet me, please be kind and don’t ask me to name my favourite tea. Instead, ask me what I love about this tea, or that tea, ask me about the feelings they evoke. Talk to me about the great variety of sensory and emotional responses instead of restricting me to a few.